Patch design is one of the miscellaneous duties of a flight crew. It has become obligatory for each crew to create a patch for their mission. Sometimes the crew commander takes an active role in the design; in other cases the commander delegates the duty of coming up with a design to one of the crewmembers. The commander always has final say on the design, of course.

Sometimes an artistically inclined crewmember may design the patch, or create a sketch which is then given to a NASA graphic artist to execute. Jim Lovell seemed to enjoy designing patches for flights he was assigned to. Mike Collins also took a very active role in the development of patches for his flights. Sometimes the crew will solicit ideas for a patch designs from others involved in the project — often including spacecraft contractor personnel. During the Gemini program, the artwork for mission patches was often created by the art department of spacecraft main contracter McDonnell Aircraft. In the early days of the Apollo program, Allen Stevens, an artist with Apollo CSM contractor North American Aviation (later North American Rockwell), did most of the mission patches.

In other cases, the crew commissions a professional artist to create their crew patch. Robert McCall was commissioned for the Apollo 17 patch; and Frank Kelly Freas for the Skylab 1 patch. In the case of a commissioned patch, the crew will generally provide some ideas to the artist regarding the themes they would like to see associated with their flight. The artist then submits a number of sketches to the crew for their feedback, and eventually produces the finished artwork. See Skylab Patchwork by Frank Kelly Freas for an excellent account of how this process works.

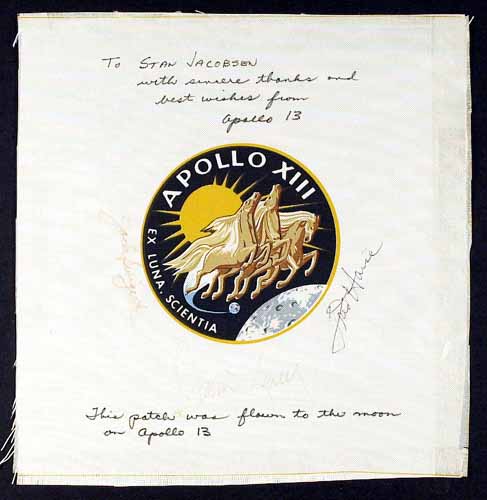

An artist doesn’t always provide the finished artwork, however. For example, while Lumen Winter created the design for the Apollo 13 patch, it was only a bas-relief roundel. This was passed on to the MSC art department, where Norman Tiller created the color version of Winter’s design. In the case of Apollo 15, Dave Scott asked Emilio Pucci to design his patch, but when Pucci provided only a roughly sketched design, Scott handed it over to the MSC art department where Jerry Elmore did the final rendering. The astronauts usually credited Stanley Jacobsen for the final patch artwork, and he was the person who got the flown, inscribed beta cloth patches (like the one shown below). In reality, Jacobsen was the head of the art department, and always handed off the actual work to someone in his crew, while he liaised with the crews.

During the Gemini program embroidered patches were sewn onto the astronauts space suits. And while the actual patches used on flights from Apollo 7 through ASTP were silk-screened onto beta cloth, for non-flight use embroidered patches were procured. These were affixed to ground-use clothing worn by the crew, worn by support and contractor personnel involved in the mission, and handed out as souvenirs by the astronaut crewmembers and high-level NASA managers.

Up until 1970, There was no standard, official contractor for embroidered patches. Various manufacturers were used, including Texas Art Embroidery, Dallas Cap and Emblem, Stylized Emblem Company of Hollywood, CA, etc. Contractors procured embroidered patches without NASA involvement, and they used other manufacturers. It was only in 1970 that MSC management decided to use AB Emblem exclusively. This provoked quite a strong negative reaction from Lion Brothers, whose management tried to influence NASA into giving them the contract by leveraging influence with Vice President Spiro Agnew, who was from their home state of Maryland.

Two companies figure prominently in the story of embroidered space patches. Both A-B Emblem of Weaverville, NC and Lion Brothers of Owings Mills, MD have made claims to being the “official” provider of embroidered emblems for pre-Shuttle manned missions. However, it appears that Lion Brothers was never utilized by NASA for mission patches, though contractors apparently procured patches from them. A standing contract was executed between NASA and AB Emblem in February 1970, and all mission patches from that time through the end of the Skylab program (including the embroidered SMEAT patches) were supplied to NASA by AB Emblem.

The issue of what patches are “official” is extremely murky, since the definition of “official” is itself very unclear. Embroidered patches were procured by NASA and the major contractors independently of each other. Different suppliers were used, even for a given mission. Some people consider patches that were given out by NASA and contractors as “official.” Based on this, some consider only Lion Brothers patches to be “official.” Yet, documents in the NASA JSC History Office Collection indisputably prove that AB Emblem was the supplier to NASA for at least the Apollo 13 through ASTP missions.

Even if being flown on a mission is considered to confer the cachet of “official,” the matter doesn’t revolve around the patch manufacturer. According to Still, astronauts sometimes carried a mix of AB Emblem and Lion Brothers patches in their Personal Preference Kits (PPKs).

The biggest difference between AB Emblem and Lion Brothers patches (aside from appearance) is that Lion Brothers stopped manufacturing patches around 1985; whereas AB Emblem has more or less continuously manufactured the patches since the time of the flight. Thus, Lion Brothers patches are more likely to be “period pieces,” or “vintage,” while AB Emblem patches could be from any era between shortly before the flight to the current day.

“The Apollo 204 review board ... recommended that non-flammable materials replace combustible ones wherever possible. ... Nylon cloth in the spacecraft and in the suits was replaced by Beta cloth, a substance developed by Frederick S. Dawn’s research team in conjunction with the Dow-Corning Company. Technically called Beta-silica fiber, it was a different material than that used in trade-name Fiberglass products. Beta-silica fibers could be spun into thin threads and then woven into fabric with a melting point of over 650°C that would neither ignite nor produce toxic fumes.” [Kozloski, p.79]

“The ITMG [integrated thermal micrometeoroid garment, the outermost component of the Apollo spacesuit] also had a Beta cloth outer layer. Scientists found that Beta cloth by itself creased easily and ripped. But Teflon added tensile strength and abrasion resistance when used as a coating over the Beta silica fiber, which was then spun into yarn. ... Intravehicular cover layers were made of two layers of woven Teflon-coated Beta silica fiber ...” [Kozloski, p.88]

“On prolonged flights, astronauts could now remove their space suits and don two-piece coveralls that afforded both comfort and protection. The coveralls, which were worn over a soft cotton undergarment, were made from Beta cloth, the same flame-resistant fabric as the space suit outer layer.” [Kozloski, p.92]

An interesting side note regarding Beta cloth developed during the preparations for the joint American-Soviet ASTP flight. Since the Soviet Soyuz spacecraft uses an earth-normal mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, they do not have the strict flammability requirements of Apollo, and therefore use wool and cotton clothing inside Soyuz. This posed a problem for crew exchange as the cosmonauts could not be allowed to enter Apollo wearing their normal in-flight garments. NASA offered to give the Soviets enough Beta cloth to produce alternative in-flight garments for the cosmonauts, but they declined the offer, opting instead to develop their own flameproof material. The fabric they developed, called Lola, proved to have superior self-extinguishing characteristics to Beta cloth. [Ezell, p.300]

It’s important to note that, as with their embroidered equivalents, when the spacesuits used on a flight are returned to Houston, the flown patches are removed from the suits, given to the astronaut who wore the suit, and replaced with unflown (but otherwise identical) patches. This practice may have originated with the earliest flights on which patches were used, as these were procured by, and presumably the property of, the astronauts who flew the missions. This was no longer the case by the Apollo era, when the patches were made from Beta cloth and procured by NASA; but the custom continued. It is worth noting that each of the Apollo 11 crewmembers declined the offer of the suit patches, and so the ones on their suits are the originals that flew on the mission.

The very first “mission” that a Beta cloth patch was created for was the 2TV-1 vaccuum-chamber mission simulation. These Beta-cloth patches were applied both to the spacesuits and to the IVA coveralls. Strangely, no Beta-cloth patch was created for the LTA-8 test, which was conducted in the same period. In that case, regular embroidered cloth patches were used. Photographs of the LTA-8 crew show these embroidered patches loosely attached to their spacesuits during preparations, but these were probably attached with Velcro, and removed prior to entry into the vacuum chamber.

The size of the patch images on the Beta cloth varied quite a lot for the first several flights on which they were used, but was finally standardized with Apollo 13. The largest of the Beta cloth patches was Apollo 8; the smallest was Apollo 12. The image below shows the variation in size.

Relative sizes of Beta cloth patches. The inner circle represents the Apollo 12 patch (the smallest of the Beta cloth patches); the light gray triangular area represents the Apollo 8 patch (the largest); and the black circle represents the standard size established with the Apollo 13 patch.

Beta cloth was manufactured by Owens-Corning Fiberglass of Ashton, RI, under contract to NASA. Owens-Corning in turn subcontracted the printing on its Beta cloth to Screen Print Corp., of Coventry, Rhode Island. The patch designs were silk-screened (using hand-mixed pigments from Roma Color of Fall River, MA) onto beta cloth 12 at a time, with a separate printing for each color. Screen Print Corp. also printed the NASA logo, the American flag (for crew wear), and crew name tags onto Beta cloth.

In addition to being worn by crew, ground support personnel and contractor personnel to signify playing an active role in support of a mission, other traditional uses of the mission patch evolved.

From the first Mercury flights through Gemini 4, Mission Control was located at the Cape. With the flight of Gemini 5 Mission Control was transferred to the newly built Mission Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas. It soon became a tradition to hang a large replica of the mission patch on the wall of the MOCR (Mission Operations Control Room) after the successful recovery of the crew. The duty of “hanging the plaque” was conferred on the lead Network Controller for the mission. Richard Stachurski recalled his experience at the end of the Apollo 11 flight in his book, Below Tranquility Base:

... The Apollo 11 mission patch, a graphic of an eagle touching down on the Moon with the Earth hovering in the black space above it, lights up the display screen at the front center of the room. Above the mission emblem are the words “Task accomplished . . . . . July, 1969.”

Just to my right, the flag-waving crowd that packs the hallway in front of the Recovery Control Room parts before the metallic clanging that heralds the incongruous appearance of an aluminum extension ladder. Dutch and one of his workmates carry the ladder to a spot about fifteen feet from the right front corner of the network controller’s console. Some of the controllers in the room take the ladder and raise it so that it reaches up to a spot high on the wall. The crowd, which had momentarily shied away from the long metal structure looming above it, surges back expectantly to surround the foot of the ladder.

Deep in an adrenaline-depletion fog, I wonder what all of that fuss is about. What the hell are they all excited about? I look up from my momentary refuge on the step, looking up past the hips and elbows of flag wavers and hand shakers. The top end of the ladder rests on the wall maybe twenty feet above the floor. It is just to the right of the Apollo 10 mission plaque. Mission plaque — oh shit, oh dear — there’s supposed to be another mission plaque high, high up on the wall — the Apollo 11 plaque.

The startling realization that the plaque has to be hung on the wall is accompanied by the terrifying awareness that I have to do the hanging. The lead network controller always hangs the damn plaque. It’s anxiety city now. My stress tolerance reservoir is dead empty. This is the one part of the mission we never trained for — no checklists, no simulations. You need me to climb up a steeply pitched ladder in front of television cameras broadcasting the event to tens of millions of viewers? Then I stumble around and try to snag a fastener of unknown configuration onto some sort of hook whose configuration is equally mysterious? A split-second vision anticipates hours of slow-motion attempts to put the thing where it belongs. The vision ends sadly with plaque and plaque hanger tumbling into the muttering, restive crowd. I see the headline on the front page of the next edition of the New York Times: “Lunar Landing Mission Ends with Single Fatality.”

“Time to get this thing up.”

Dave Young’s voice interrupts my apocalyptic vision. He shoves the blue and gold mission plaque into my reluctant hands. Seeing my hesitation and the I-don’t-really-think-I-want-to-do-this look on my face, he applies the ultimate stimulus, “Ernie Randall said he’d be glad to do this if you don’t.”

“OK, OK.”

I grab the plaque in sweating palms and start toward the foot of the ladder. I put my right foot on the first rung and hope I don’t slip. A burst of cheers and applause accompanies my first shaky step up the ladder ...

My second step is so shaky that a young woman standing near the foot of the ladder says, “You better let me help,” as she instinctively reaches out to give me a little shove in the middle of my lower back. Pushed up by that sympathetic touch, I finally reach plaque-placing altitude. I take a quick glance at the back of the plaque and then at the wall to see what I have to hang on what. Reaching out with trembling hands, I slide the plaque down the wall toward the intended hanger until I feel what I think is a contact. Gingerly I release my grip on the plaque. Dumb luck prevails the thing stays in place on the wall. The cheers of the crowd drown out my murmured prayer of thanks to the gravity gods. I back down the ladder and plant my feet on the deck. My part of this mission is done.

Beginning with Apollo 7, an image of the crew patch was placed on the door of the crew transfer van which carries the fully suited flight crew, from the crew quarters building to the launch pad. Below is a photo of Steve Tatham, the driver of the crew transfer van.

Clearly someone noticed that when the crew entered the van, the patch — which on the outside of the door — was not visible. So beginning with Apollo 8, the crew patch was displayed on the inside of the door as well.

For internal-use publications, the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston had a standard cover that carried a bit of symbolic artwork at the bottom essentially symbolizing “Earth to Moon” — more or less the raison d’être of the center. When the center was renamed in 1973 to honor President Lyndon Johnson, the standard cover was redesigned, and in place of the previous artwork, a modified version of McCall’s Apollo 17 patch was used.